I’ve booked a ‘profit’ of £300 with RECI.

Now undecided to add to RECI or not.

Investment Trust Dividends

I’ve booked a ‘profit’ of £300 with RECI.

Now undecided to add to RECI or not.

Gore Street Energy Storage Fund plc

(the “Company” or “GSF”)

1 pence dividend declared, with an additional special dividend of 3 pence expected when proceeds from the sale of the Big Rock investment tax credits (“ITCs”) are available for distribution.

Residential Secure Income plc

Dividend Declaration

Residential Secure Income plc (“ReSI)”, or the “Company“) (LSE: RESI), which has invested in independent retirement living and shared ownership to deliver secure, inflation-linked returns and is now implementing a managed wind-down strategy, is pleased to declare an interim dividend of 1.03 pence per Ordinary Share to be paid in the financial year to 30 September 2025.

UIL LIMITED

Third quarter dividend declaration

The Board of UIL Limited has declared a third quarterly interim dividend of 2.00p per ordinary share in respect of the year ending 30 June 2025, which will be paid on 29 August 2025 to shareholders on the register on 8 August 2025. The ordinary shares will go ex-dividend on 7 August 2025.

US Solar Fund PLC

(“USF”, or the “Company”)

FIRST QUARTER UPDATE

US Solar Fund plc (LON:USF (USD)/USFP (GBP)), the renewable energy fund investing in utility-scale solar power plants across North America, is pleased to release its first quarter update for the period ended 31 March 2025.

Highlights for the quarter to 31 March 2025:

NAV update:

· USF’s unaudited NAV as of 31 March 2025 is $196.6 million ($0.64 per share) which represents an increase of approximately 1.3% from the audited NAV as of 31 December 2024

· The movement in NAV reflects the roll-forward of the valuation models and adjustments to portfolio working capital over the period

Dividend update:

· Dividend of 0.56 cents per Ordinary Share for Q1 2025 to be paid by 4 July 2025, in line with the Company’s existing annual dividend target of 2.25 cents per share

· On 17 April 2025, the Board announced an increase in the annual dividend target from 2.25 cents per share to 3.5 cents per share, which will take effect in Q3 2025

Portfolio performance:

· Generation by the Company’s portfolio in the first quarter was 9.1% below forecast (-11.6% for Q1 2024), with +2.2% attributable to favourable weather and -11.3% attributable to technical (non-weather) factors

· Performance during the first quarter was impacted by unplanned outages, particularly at the Heelstone and Granite portfolios. This was related to technical issues, as well as planned outages timed to allow maintenance activities to be completed during the lowest production quarter of the year and ensure equipment longevity

· Ongoing initiatives to manage and remediate technical issues to reduce the occurrence and length of unplanned outages continue to be implemented as part of the remediation plan developed by the Investment Manager’s asset management team

Current yield 5.8%, neither belt or braces so not in the watch list.

Brett Owens, Chief Investment Strategist

Updated: June 10, 2025

BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, is turning its back on long-term Treasuries—and that’s rattling the bond market.

That, in turn, has the mainstream crowd turning its back on ALL bonds.

Mainstream crowd turning its back? That’s all we need to hear! In a second, I’ll reveal a 9% “contrarians only” dividend that’s tailor-made for this critical time in Bond-land.

First, let’s break down what the global investment titan is telling us here: In its weekly commentary, released June 2, BlackRock laid things out in stark terms (or at least as stark as a stuffy financial institution gets!):

“Our strongest conviction [bolding mine] has been staying underweight long-term US Treasuries.”

Then the real kick in the teeth: “We prefer the euro area to the US.” Ouch.

BlackRock’s not alone in turning up its nose at long-term government bonds. DoubleLine Capital, led by “Bond God” Jeffrey Gundlach, is turning away, too—especially when it comes to the longest of the long bonds:

“Where we can outright short [30-year Treasuries], we are,” one of the firm’s portfolio managers recently said.

We’re talking about 30-year Treasuries here. Invest for three decades and get your cash back at maturity, with a steady payout kicked your way every year.

Till now, these have been seen as among the safest of the safe investments. Yet as I write this, investors are demanding a near-5% yield to take on the “risk” of owning them!

Bond Panic Is Our Opportunity—in These 9%-Paying Funds

All of this—not to mention weak demand at a recent 20-year government bond auction—has investors fretting over bonds, corporate and government alike.

We, meantime, are targeting select corporate bond closed-end funds (CEFs) like the one we’ll name below, quietly kicking out yields of 9%, 10% and more. Let’s get into why, starting with Uncle Sam.

It’s not hard to see why investors aren’t keen to boost his credit line. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO)—famous for its rose-colored glasses—has already projected a $1.9-trillion deficit for 2025.

This leaves the government with a $40-trillion debt hole, deepening by $2 trillion a year. Congress is also working through the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which the CBO estimates will add $2.4 trillion to deficits over the next decade. And, of course, Moody’s recently lowered America’s credit rating.

With buyers of government debt thin on the ground, long-term government bond yields are rising (and prices are falling, as yields and prices move in opposite directions). That’s a giant red flag for all bonds, right?

Bessent’s Making Quiet Moves to Curb Rates Now …

While this interpretation isn’t exactly wrong, it focuses too much on the numbers and not enough on the human factor, specifically Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Fed Chair Jay Powell—or more specifically, Powell’s likely successor.

Let’s start with Bessent, who has straight-out said he wants to lower the 10-year Treasury rate—pacesetter for consumer and business loans. He’s got plenty of tools at his disposal, including leaning more heavily on short-term debt to fund the government.

That limits the supply of “long” bonds, offsetting future lame auction demand and driving up bond prices (while reducing their yields). This is something Bessent criticized former Treasury Secretary Yellen for doing. But he’s been quietly keeping it up.

Finally, we’ve got an administration fixated on tariffs (which slow growth) and lowering energy prices. It won’t take much extra drilling to pull off the latter—WTI crude is already on the mat, at $63 a barrel as of this writing, on rising OPEC production.

Slower growth + lower oil = lower inflation (and lower rates).

… While the Fed Warms Up in the Bullpen

Then there’s Jay Powell, who, yes, has been holding off on rate cuts. (Jay controls the “short” end of the yield curve, the rate banks charge each other for short-term loans.)

But Jay’s term ends in 11 months, and it’s highly likely the administration will appoint a successor who would work with the government to reduce rates. Lower “short” rates would act as a weight on long rates, helping push bond prices higher.

The Bond God’s Favorite 9% Dividend Is Built for Times Like These

All of this is a prime setup for high-yield corporate debt, which is being shunned along with the federal government’s credit. A top play comes from the Bond God himself: the DoubleLine Yield Opportunities Fund (DLY).

As I write this, DLY yields 9%, and its real strength is its wide mandate—Gundlach is free to invest in any form of high-yield credit, anywhere in the world.

That’s what we want: This bond savant unchained and working for us!

He’s taking a smart approach, too, keeping most of DLY’s portfolio (just under 70%) in high-yield corporate bonds, mortgage-backed securities (which despite the fact that they touched off the 2008 financial crisis are highly regulated today), emerging-market debt and a range of other debt instruments with durations of three years or less.

That’s a prudent setup, as shorter-term bonds still kick out strong yields and won’t be hit as hard as longer-term bonds if rates stay stuck at these levels for a while, or even rise. It also frees up Gundlach to reinvest faster as the rate picture shifts.

Beyond that, since Gundlach can invest across the globe, DLY can benefit as more capital, spooked by Uncle Sam’s bloated budget, hunts for yield abroad.

As I write, DLY trades at a 0.6% discount to net asset value (NAV, or the value of its portfolio) down from a roughly 1.5% premium earlier this spring. The fund also pays that 9% annual dividend with monthly distributions. It has paid special dividends in the past, too.

DLY’s Smooth Monthly Payout

Source: Income Calendar

The bottom line? With Bessent working to bring down rates now, and more help likely from the Fed down the road, we’ve got a flexible setup for income and upside, guided by Gundlach himself. Let’s buy before this discount grows into a healthy premium.

A favoured share for the Snowball, although if you wanted to achieve a 7% blended yield, you would have to pair trade it with a higher yielder. Another opportunity that the Snowball failed to buy, although it did make a profit of £732 trading another dividend hero MRCH.

The Snowball is building a rainy day fund, so maybe one day it can buy LWDB but looking at the chart, not for a while, which is a plus as it will allow time for more funds to be added to the rainy day fund. There will be around 2k of income to be re-invested into the Snowball this month, most probably in RECI.

Both shares paying above average market yields.

But using only the information provided by the chart, again with the benefit of good ole hindsight, which share would you had the greatest chance of making a capital gain along with your dividend income if you research was wrong ?

09 June 2025

Orbis takes a cautionary look at market concentration, investor herd behaviour and the importance of stepping beyond the obvious in search of lasting value.

By Orbis Investments

In today’s investment landscape, the dominance of the US – especially a handful of mega-cap technology companies – is hard to ignore. These firms have powered a disproportionate share of global equity market returns in recent years and the US now accounts for around 75% of the MSCI World index. The so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ have captured investor imagination and capital alike. But when nearly everyone is crowded around the same trade, it’s worth asking: what if we’re all looking behind the wrong door?

Enter the Monty Hall problem. This classic probability puzzle, loosely based on a 1970s game show, involves a contestant picking one of three doors. Behind one is a car, behind the others, goats. After the contestant picks, the host (who knows what’s behind each door) opens one of the remaining doors to reveal a goat. The contestant is then given the option to switch. While most stick with their initial choice, switching actually doubles the contestant’s odds of winning the car!

The puzzle is a compelling metaphor for today’s markets: just because something feels obvious – or has worked recently – that doesn’t make it the right choice in future.

Lesson 1: The obvious choice isn’t always the best one

On the surface, staying heavily invested in US equities looks sensible. It’s the world’s largest economy, home to dominant companies, and it has outperformed for over a decade.

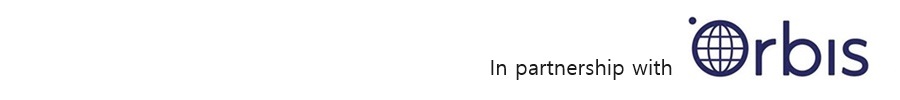

But history reminds us that market leadership shifts. In the late 1980s, Japan made up more than 40% of the global index before its bubble burst. Similarly, the dot-com crash of 2000 exposed the perils of speculative excess in the technology, media and telecoms sectors. Both events were obvious in hindsight, but herd mentality and a fear of missing out clouded judgements at the time.

Source: FTSE, Orbis. Image Source: Grantuking via Wikimedia Commons. Benchmark data is for the FTSE World Index. Statistics are compiled from an internal research database and are subject to subsequent revision due to changes in methodology or data cleaning. Data shown through to January 2002 to show subsequent peak to trough decline.

Today’s US equity market shows signs of similar concentration and froth. President Trump’s renewed tariff threats have unsettled markets as well as global supply chains, and fresh US export restrictions on chips to China prompted warnings from Nvidia about billions in lost revenue. Meanwhile, valuations remain stretched.

For a generation of investors raised on uninterrupted American outperformance, it may be time to reassess where the real risks – and opportunities – now lie.

Source: LSEG Datastream, Orbis. Relative total return of the DataStream US Market versus DataStream World ex-US Market indices.

Lesson 2: Insight matters – but only if you act on it

Spotting market dislocations is one thing, acting on them is another. Investors may sense that sentiment is frothy but going against the crowd is always difficult. It’s particularly hard when the prevailing narrative is that “AI is the tide that will lift all boats” and investors are surrounded by highly speculative activity being wildly profitable.

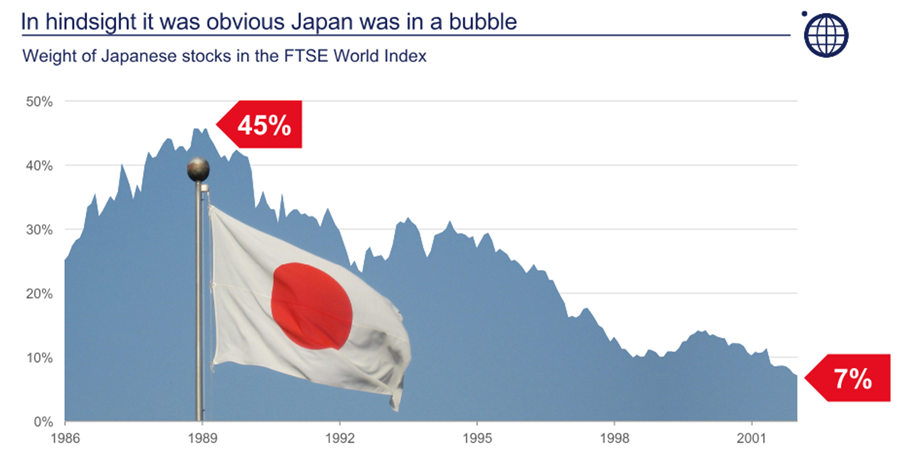

At the end of 2024, cryptocurrencies and digital tokens were valued at $3.3 trillion – up 96% in a year. In a sign of the times, ‘Fartcoin’ which was launched in October ended 2024 with a market cap just shy of $1 billion. That’s more than three times the peak valuation of Pets.com, the dot-com bubble’s poster child, which managed to go public and go bankrupt in the same year back in 2000.

Source: CoinGecko, Cryptocurrency logos. *Total market capitalisation of all cryptocurrency.

Meanwhile, US hyperscalers have been ramping up capital expenditures to chase AI dreams – with no clear line of sight to monetisation. Their ratios of capex to sales are rising sharply, and it’s not clear that returns will justify the outlays.

And that’s the crux of it: markets aren’t always efficient, especially when investors are chasing hype over substance. As the Monty Hall problem teaches us, knowing the odds isn’t enough. You need to tune out the noise and have the conviction to switch, even when it feels uncomfortable.

Lesson 3: Nothing is certain – apart from death and taxes

Even with the optimal Monty Hall strategy, contestants only win two-thirds of the time. In investing, research shows that even top-tier managers only get it right about 60% of the time. That’s why broad and thoughtful diversification across sectors, geographies, and styles is so valuable.

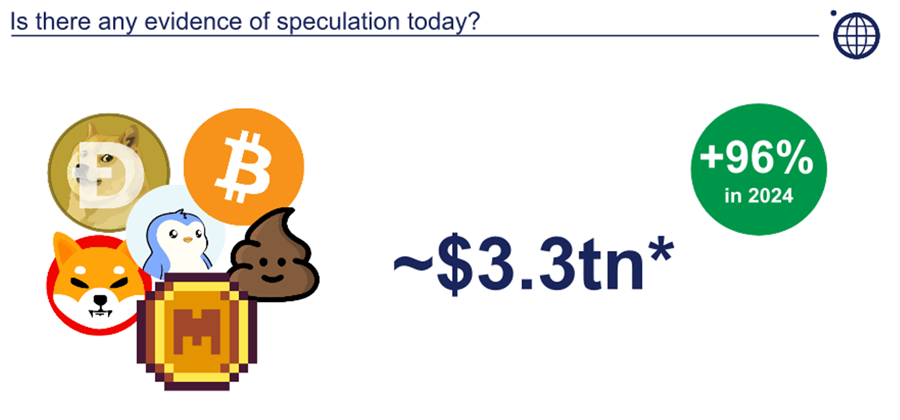

Many investors today believe they’re diversified because they hold global index trackers. But with US stocks now making up nearly 75% of global benchmarks like the MSCI World index, many portfolios are far more concentrated than they appear. That concentration is made more problematic by valuation levels. The S&P 500 trades at around 23 times forward earnings – well above its historical average and significantly more expensive than global markets, which average closer to 14 times. This discrepancy suggests that investors might be paying too much for the comfort of familiarity.

Source: LSEG Datastream, Orbis. World ex-US is the Datastream World ex-US Market Index. US is the Datastream US Market Index. Calculated using I/B/E/S consensus 12-month forward earnings estimates.

Meaningful diversification is about holding assets that behave differently and the benefits are felt most when the prevailing market trends reverse. Investors need to ask whether their portfolios are truly positioned to weather regime changes. And if they aren’t, what’s stopping them from switching?

Reframing comfort zones

The Monty Hall problem teaches us that the obvious answer isn’t always the correct one. The same holds true in investing. Sticking with the US and big tech may have felt safe, until very recently at least, but sticking with what’s familiar can offer false comfort. In today’s environment, defined as it is by extreme market concentration and investor herding, the real edge lies in having the conviction to take a different path.

Ultimately, investors must always be sceptical about simply following the prevailing market consensus, as current prices already reflect those views. Proper diversification today also requires going beyond simply mirroring global benchmarks.

Just as switching doors improves your chances in the Monty Hall problem, being willing to look beyond the obvious and focus on where value is being overlooked is the key to long-term success in investing.

How gilts can help you pay less tax on savings interest

Helen Saxon

Edited by Gary Caffell

Updated 9 September 2024

If you pay tax on savings interest, and you’ve already maxed out your cash ISA for this tax year, investing in specific gilts (also known as government bonds) could shelter more of your cash from the taxman. In this guide we take you through what gilts are, how this trick works, and how to buy gilts. We’ve even developed a quick gilts calculator to help you compare returns to normal savings…

This is the first incarnation of this guide. We want to thank Sam Benstead, fixed income lead at Interactive Investor for helping us fact check it. Note that this guide doesn’t constitute financial or investment advice and – as with any investment or new financial product – you should always do your own research to make sure it’s right for you.

What is a gilt?

Governments have two main ways of raising cash to pay for public services. The first is to tax the population, which is generally unpopular. The second is to borrow, which is generally more popular, though comes with its own downsides. One way the UK Government borrows is to sell debt, and one way it does this is by issuing gilts.

These gilts – also known as UK government bonds – can act a lot like fixed savings accounts, particularly if the gilt is maturing within a couple of years. At the start, you put money in (to do this you buy the gilt, usually through an investment platform – more on the different pricing structures below). But, instead of the cash sitting with a bank, you are effectively lending it to the Government.

In return the Government promises to pay you regular interest while you hold the gilt. This is known as the “coupon” or “coupon rate” and will be listed prominently on all gilts.

And, as you might expect, when the gilt reaches its maturity date, the Government pays back the lump sum it borrowed, which is £100 per gilt (though you might have paid less for it). So, you’ve your money back, likely plus a bit extra if you bought at a discount. And you also get the interest (coupon) you’ve made during the period you held the gilt.

Are gilts safe to invest in?

As gilts are issued by the UK Government, they are seen as safe. The UK Government has never yet defaulted on gilt repayments or coupon payments.

However, there is some risk. If the UK was to go bankrupt, then there’s a chance the government of the day wouldn’t have the cash to pay you back when your gilt matures. Though it’s likely that if such a thing were to happen, we’d all have bigger problems anyway.

That said, like any savings account or investment, it’s best not to put all your eggs in one basket. If you do choose to invest in gilts, for safety it should only form part of your savings strategy. If you’re not sure what to do, or whether this is right for you, seek help from an independent financial adviser.

A quick glossary before we continue…

If you’re new to gilts, then there are a few terms you’ll need to understand before reading the rest of this guide…

Coupon: this is a fixed interest rate the Government pays to the gilt’s holder. It’s usually paid twice a year on fixed dates six months apart. For example, a 10-year gilt with a face value of £100 and a coupon rate of 3% would pay out £3 each year.

Maturity (or par) value: the amount of capital you’ll receive when when the bond reaches its full term. Most gilts are redeemed at a face value of £100 when they mature.

Maturity date: when the bond matures and the Government pays the gilt holder the maturity value. On this date, you’ll receive the final coupon payment and the principal capital amount back. For example, if you hold the gilt “TREASURY 0.125% 30/01/2026” it will mature at the end of January 2026.

How can gilts help me pay less tax on savings?

The ‘What is a gilt’ section of this guide above assumes you buy the gilt at full price at issue and hold it to maturity. Which can work, but often isn’t tax efficient as you pay tax on the coupon.

Instead, there’s another way – buying low-coupon gilts at a discount via an investment platform and holding them to maturity. This is more tax efficient, as the gain isn’t subject to tax (not even capital gains tax). Here’s how it works:

Buy a low-coupon, short-term gilt at a discount. The gilts that have been popular in realising this tax-efficient gain are mainly those issued during the pandemic and coming to maturity in the next year or two.

Get the coupon while you hold the gilt. The coupon payment(s) is counted in the same way as savings interest for tax purposes. So, if it comes under your Personal Savings Allowance, it’s tax-free. If you’ve already gained enough interest from other savings that you’ve used this up, then you’ll pay income tax on the coupon at your marginal rate.

Hold it to maturity and realise the capital gain. Gilts are a special case as, unlike most normal bonds, any value gain you make on them isn’t subject to capital gains tax, and doesn’t count towards your CGT allowance (£3,000 in the 2024/25 tax year). This is true whether your capital gain is from holding gilt(s) to maturity, or selling it for more than you paid for them.

Using gilts in this way is tax-efficient, as it minimises the amount you’d need to pay in income tax on savings, but maximises the amount you can earn tax-free as a capital gain.

Here’s how this could work in practice… (prices correct at time of writing; always do your own research on current prices and use the calculator below to see the annualised return and whether savings are likely a better option).

Gilt T26 matures on 30 January 2026. It has a coupon of 0.125% and a price of £95.04. Buy it at that price and hold it to maturity and you’ll get £100 capital back in January 2026. You’ll also have made between 10p and 19p on the coupon (depending on your tax rate). This is an annualised return of around 3.6%.

While this doesn’t seem a lot, if you pay even basic-rate tax on savings interest, you’d need a savings account paying 4.75% to get the same return after tax. For higher-rate, it shoots up to 6.33% (additional 6.91%) – and those rates definitely aren’t out there.

Important: Know the difference between ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ gilt pricing

The ‘clean’ price of a bond (the one you’ll see quoted on gilt price listings) is its price without accrued interest. Yet it may not be the price you end up paying.

This is because you may need to compensate the gilt’s current holder for any coupon amount accrued – but not paid out to them – at the point you buy. The price you pay which incorporates this amount is known as the ‘dirty’ price. This mechanism allows gilt holders to be certain they’ll get the coupon payment due for the time they hold the bond, irrespective of when they choose to sell.

If you buy a bond immediately after the latest coupon has been paid (usually this is every six months), the clean and dirty prices will be the same.

Investment platforms tend to list the clean price for easy comparison between bonds, but be aware the amount you actually pay may be slightly different.

© 2026 Passive Income Live

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑