The Analys

The best stocks in Britain’s diverse energy sector

Former City analyst Robin Hardy assesses the opportunities among energy delivery companies

Published on October 1, 2025

by Robin Hardy

The UK-listed energy is a large and diverse collection of both pure businesses and collective investment funds focusing on one or more points on the energy delivery spectrum. It encompasses a wide set of aspects of the energy market from upstream to downstream, from clean to dirty, from new technology to old, and from generation to supply. There are businesses offering potentially rapid growth through to plodding, near utilities and also some of the UK market’s larger dividend yielders. That means investors in this sector are capable of generating a diverse range of earnings streams that should suit pretty much any approach or ESG standpoint. While the sector is large by market cap terms, that value is heavily skewed to a handful of some of the UK’s largest stocks.

We start with a ‘view from 10,000 feet’ of how this diverse sector fits together.

The oil & gas sector

This remains, by some margin, the largest part of the energy sector due to FTSE giants Shell (SHEL) and BP (BP) (combined market cap >£200bn). Understandably this remains a problematic area for many investors due to its negative environmental credentials, although this is likely to be where the greatest investment in green energy will be found. These businesses are looking to salve their reputation and avoid future punitive taxation and they have immense free cash flow to slowly move their business models away from fossil fuels. We have written in this column before that perhaps the best route to clean energy is to buy dirty.

Shell’s appears the stronger and more consistent approach to building a more balanced future energy profile, while BP has back-peddled: this is reflected in a different share price performance with Shell delivering the greater gains over the past five years.

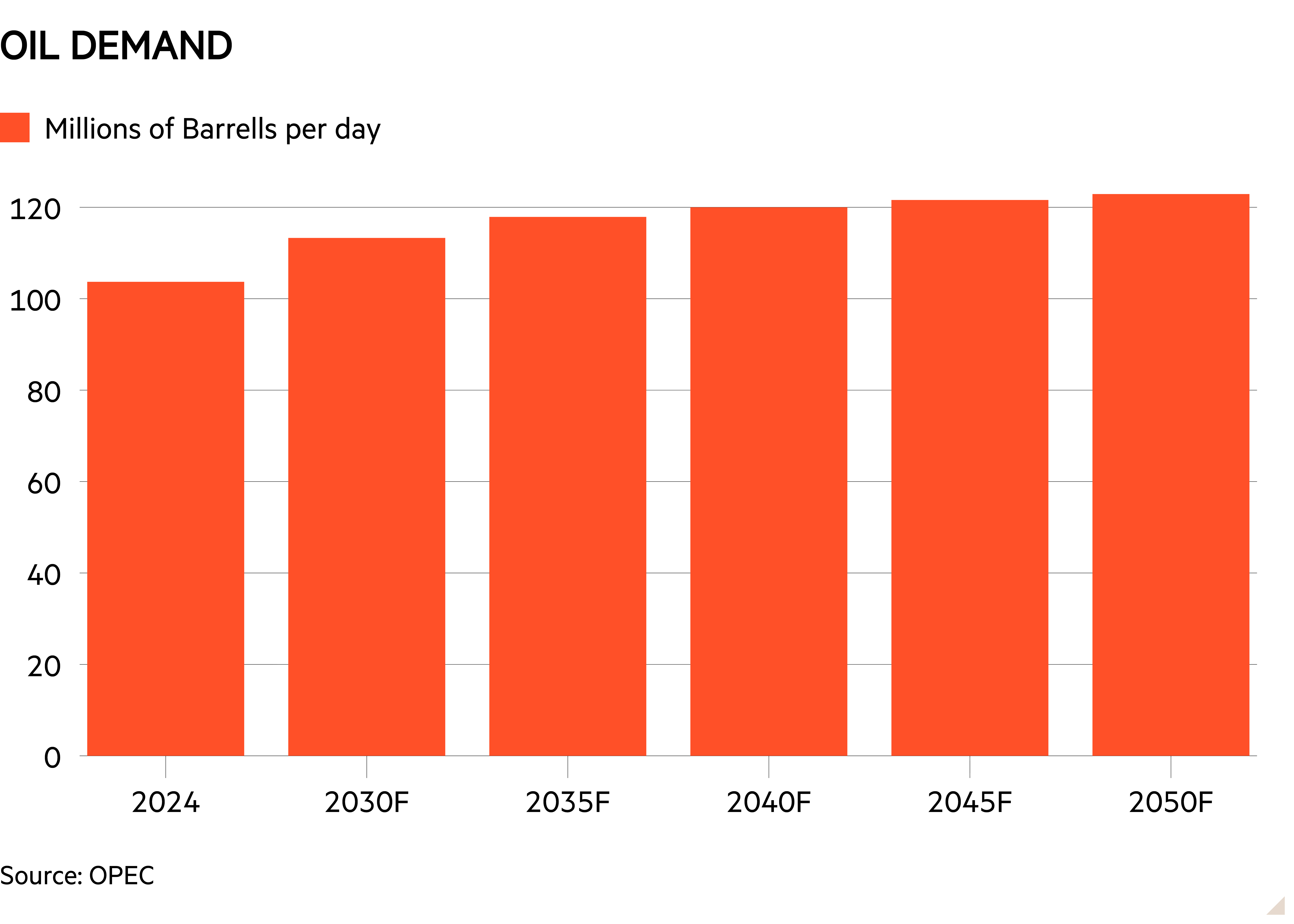

While investors may wish to focus on green energy, there is no escape from the fact that the outlook for oil demand remains strong. Even by 2050 global demand for oil is forecast to be close to 20 per cent higher than it is today: 123mn barrels per day versus 2024’s 104mn. In a less stable geopolitical climate oil prices are likely to remain volatile but relatively high, allowing for very healthy profits to still to be generated from fossil fuels. These earnings may be fairly lowly rated but they are extensive and growing.

In the oil and related space, in addition to these large integrated businesses (upstream and downstream) we also have pure upstream businesses such as Tullow (TLW) and Harbour (HBR) through to Aim-listed exploration-only businesses such as Rockhopper (RKH), although a good number of smaller Aim-listed players have more recently de-listed from this UK’s junior index. These smaller stocks are typically riskier and more volatile in nature and most have not generated good returns for investors.

The clean energy sector

Clean or renewable energy comes in four core variants: wind, solar, biomass and fuel cell technology. We are not counting nuclear energy here although this is technically a renewable source.

Fuel cell technology

Fuel cell technology is a clean rather than renewable energy source as it consumes and converts an input material. It is the process of turning either methane (natural gas) or hydrogen into electricity by means of hydrolysis. As this is a fully reversible process, it can also be used to store power by turning electricity into hydrogen, potentially very useful in systems such as wind where some kind of network storage/battery is ideally used to capture excess power generation.

The problem with fuel cells is their relatively low output, often making only enough power for a single building, factory or large vehicle: this is not really a technology for network generation. The largest potential installations might run to 100MW, enough to run a single large factory at peak load. However, as power generation is moving increasingly to the micro or local scale, there is a clear space in the market for this technology.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

Another potential issue for fuel cells is that the production of the cleanest fuel cell fuel, hydrogen (the only byproduct is water), is not typically a clean process. Most hydrogen (around 96 per cent) is made using steam methane reforming which can release significant amounts of carbon dioxide. But green hydrogen production (using renewable energy and electrolysis) is rising steeply.

The problem for investors with this sector is that the listed players are small: ITM Power (ITM) generates less than £50mn revenues and Ceres Power (CWR) nearer £30mn with neither yet generating positive EPS. That said, running from such a low revenue base does allow for sharp share price movements whenever a sizeable supply contract is signed, but also equally negative reactions come when delays occur, which appear common. Making money in this space is challenging.

Renewables

Renewables is a reasonably hard sector for investing in single stocks, but there are 18 renewable energy investment trusts trading on the LSE.

Wind

There is limited scope for direct investment here with the only pure play being investment trust Greencoat UK Wind (UKW). This sector attracts the particular ire of US President Donald Trump and given the recent UN speech and the economic levers Maga likes to pull to impact policy globally, this sector may face a tough near-term future. There are also concerns about long-term operational costs and the unpredictability of generating levels. Wind (mainly offshore) in the past 12 months contributed around 30 per cent of the UK’s electricity. But investors’ options are limited, with the perhaps best routes being tangential through overseas operators, funds or the likes of turbine manufacturers.

Solar

Again, single company investments are limited here but funds/trust abound. The largest options here are The Renewables Infrastructure Group (TRIG) which is also involved in wind, SDCL Efficiency Income (SEIT), Foresight Solar Fund (FSFL) or Bluefield Solar Income (BSIF). Share price performance in recent years has not been great but yields in all four cases are close to double digits and are generally high across this subsector. This, however, reflects some higher levels of risk, as do the material discounts to asset values.

Biomass

Biomass involves the burning of, primarily, waste or byproducts in the form of methane from food waste or – the largest and perhaps most controversial source – timber. The main player here is Drax (DRX). Drax is a single, converted coal-burning power station that now burns wood pellets made in a fully vertically integrated, wholly owned supply chain based mainly in North America. There has long been controversy about the burning of wood as a green/clean energy source (it releases captured carbon and produces particulate matter) plus specific issues about the wood Drax burns. Here the group has been accused of “greenwashing” (it claims to burn only waste wood, forest clearings and ultra-low quality trees) but there have been suggestions that it also burns higher quality wood.

Hydro

Globally, hydro is a key generating source (15 per cent) but is tiny (at below 2 per cent) in the UK with only a couple of facilities within SSE’s portfolio. Here it is largely for power storage or emergency infill rather than core generation and this is unlikely to change.

New generation energy

This is something of an adjunct from the clean sector and largely points to the small modular reactor (SMR) sector. Nuclear can still be an issue for some investors but this exciting new generation sector gives a relatively rare opportunity to invest in nuclear generation. Nuclear is more typically a state-funded sector with power stations costing perhaps £50bn but SMRs (according to Rolls Royce (RR), the only substantial UK player) will start at £1.8bn and likely reduce as volumes rise. This subsector should play a major role in the decentralisation of power generation. While capital costs are higher than wind generation, long-term use costs are likely to be materially lower with much longer lifespans.

Generation, supply and distribution

This is the more stable, utility-style end of the energy space where low competition, even monopoly positions allow for more defensive investments but more typically without the scope for substantially market beating returns. This was also historically where one would have come for high yields and metronomic dividend performance. The turbulence in large-scale energy markets in the last five years has allowed much stronger share price performance but this is largely anomalous and for many this is still a subsector best targeted for long-term income returns.

However, the changes in the energy profile of the UK have led the players in this space to swing their free cash flow profile away from their historic position of having almost literally nothing else to do with their surpluses other than reward shareholders. Now large capital investment programmes such as National Grid’s (NG) £60bn+ grid renewal and localisation are changing capital allocations and in the process are likely to change these stocks from an income bias to something more akin to growth/income. This should raise likely total shareholder returns from mid-single digit percentages to high single, perhaps even low double digit.

Supply

There is relatively little for investors to play here with the bulk of the big six suppliers (British Gas, Octopus Energy, E.ON Next, OVO Energy, EDF Energy, and ScottishPower) either privately owned or part of international businesses. The only UK-listed access is for British Gas which is around half of Centrica (CNA), so this sector is essentially a closed avenue today for direct investment.

Generation

The only substantial generator listed in the UK is SSE (SSE) which is increasingly focused on green energy, while retaining capacity in gas powered facilities: its gas capabilities remain larger than its wind capacity but by 2027, this should have reversed. It is also a grid operator/distributor in Scotland. Drax is a single location generator, while nuclear power in the UK is controlled by France’s EDF (unlisted) with the balance of gas powered output not run by SSE being in the hands of Germany’s RWE (DE:RWE).

Distribution

The UK gas network is owned by a consortium of private equity investors, while the electricity network remains largely within listed businesses. National Grid (NG) operates the whole of England and Wales with SSE running part of the Scottish system alongside Spain’s Iberdrola (ES:IBE). NG has been described as “reassuringly dull” as the UK grid has to operate, and customers have to pay for it. With the UK power system increasingly decentralising, that could be under threat, but NG is seizing the opportunity to play a major role in the switch to local generation and distribution. The market seems to believe that it might just work. Perhaps less rosy is that operations in the US now deliver two-thirds of the group’s earnings and policy in that market is looking to favour fossil fuels over green generation.

SSE too has sought to change its spots and has more than once cut what was once seen the UK’s safest dividend to instead fund growth, mainly in renewables. While it may not massively increase its total power generation in this process or be able to charge customers more, the market values wind electricity much more highly than gas electricity so investors should win.

A potential fly in the ointment for these former utilities is their capital structure, especially in NG’s case, using higher debt levels within their capital base (akin to the issues in the water sector). Heavy spending on transition will probably see debt rising further. The days of cheap money are over and this capital structure risks being a drag on growth.

I’ve been exploring for a bit for any high quality articles or blog posts on this kind of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Reading this info So i’m happy to convey that I have an incredibly good uncanny feeling I discovered just what I needed. I most certainly will make sure to don’t forget this website and give it a look on a constant basis.

Undeniably consider that which you said. Your favourite justification appeared to be on the internet the simplest factor to remember of. I say to you, I certainly get annoyed while other people think about concerns that they just do not understand about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and defined out the whole thing with no need side-effects , people could take a signal. Will likely be again to get more. Thanks

It’s actually a nice and helpful piece of information. I’m happy that you just shared this helpful info with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

There’s noticeably a bundle to find out about this. I assume you made sure nice points in features also.

This really answered my downside, thanks!