Income:

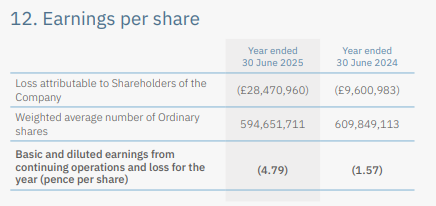

Obviously, the question turns to well, are these assets really worth £1.1m per MW? Or more? They were worth 12% more last year ….. £1.24m per MW at 30/06/24 and a lower revaluation due to power prices were the main reason for the NAV to drop and for BSIF to record a loss in FY25.

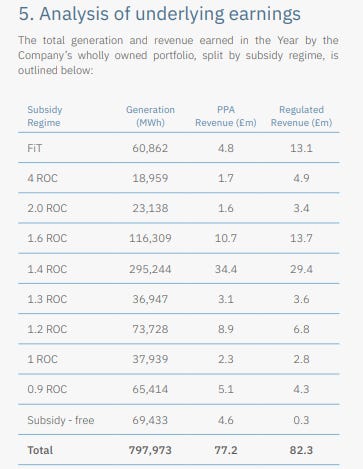

Income Analysis:

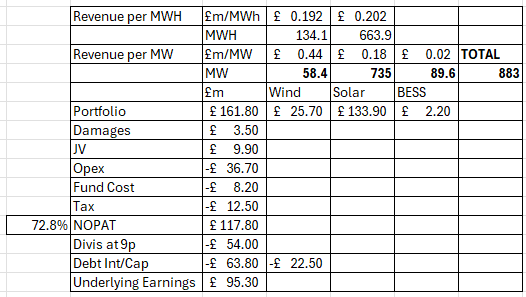

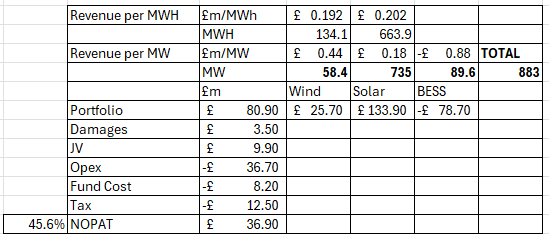

Those assets delivered £161.8m of revenue in FY25, varying between £0.44m per MW for Wind and £0.18m per MW for Solar.

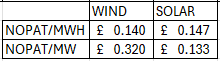

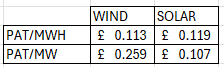

If you consider net operating profit after tax was 72.8% then the assets delivered £0.14m – £0.147m per MWH which is a price divided by pre-interest earnings of 7.5X – 8X.

Now, you’ll notice I’ve gone with NOPAT – net operating profit after tax – but avoided interest costs. That’s deliberate because I wanted to see the earnings relative to the enterprise value and EV/EBITDA is too crude.

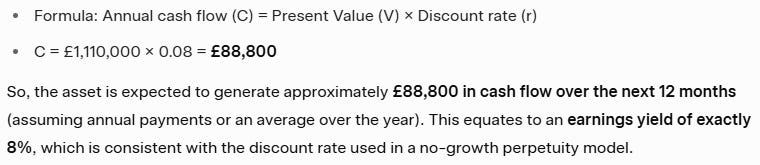

£140,000 per MW is far higher than what the Discounted Cash Flow approach to calculating NAV would imply a 55% upside:

In case you’re curious, the NAV is about 25% higher once you use PAT discounted at 8%.

Of course my calculations assume a flat income based on the prior year numbers. Power Curves and Inflation are increasing and reducing forces.

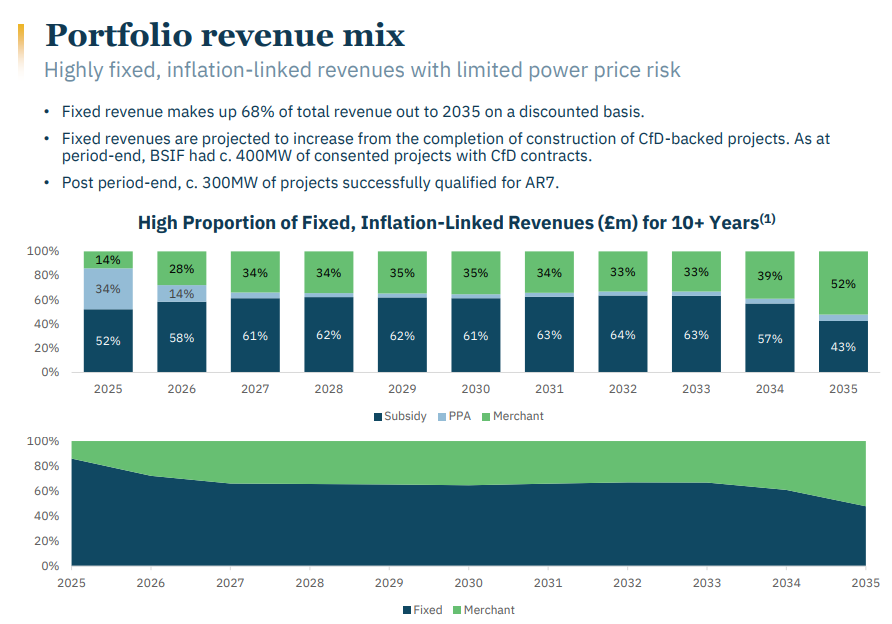

On one hand, RPI assumed at 3% boosts revenues until 2032. That’s how the subsidy reaches 64% that year. BSIF is a beneficiary to inflation. (Although refer to undermined confidence later)

Along with most other electricity generators BSIF is dogged by the 3 leading power forecasters who believe that electricity prices will fall in the period 2025-2030.

Their 2025 forecasts – as usual – have failed, and prices have been rising since early 2025 and stand at £85/MWh as I write vs the £65/MWh they “forecast”.

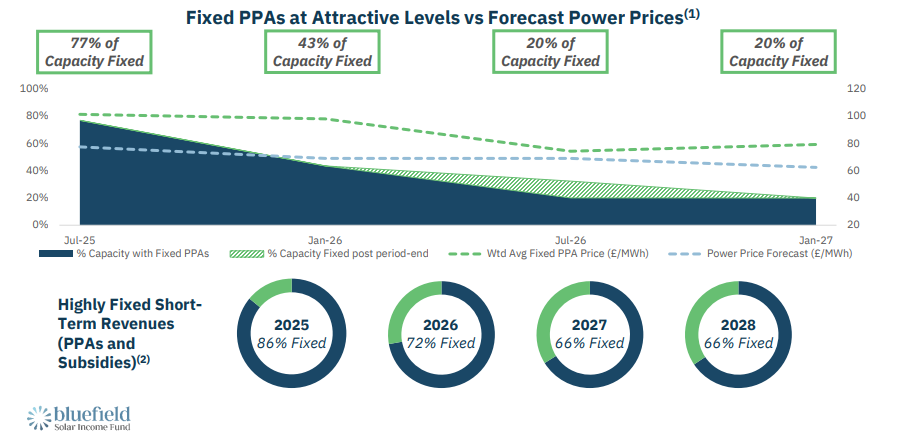

In any case, BSIF lock in 1 year to 3 year PPAs to insulate themselves just in case one day their forecasts end up being in any way accurate.

Undermined Confidence in Renewables

Now it’s also true that while electricity have NOT dropped, renewable electricty producers’ share prices HAVE fallen including at BSIF. Why? That is due to everyone’s favourite politician, Ed Milli.

The government recently threatened to do the dirty on the renewables sector, altering their contracted income and moving their increases from RPI to CPI. Good old Milli, moving the goalposts just like a tinpot republic would – never too far away from courting disaster.

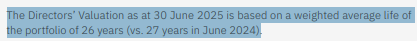

Since the remaining average life of assets at BSIF is 25.5 years the impact if the simple switch approach is taken would be 2% of NAV while the harsher freeze approach would impact NAV by around 8%.

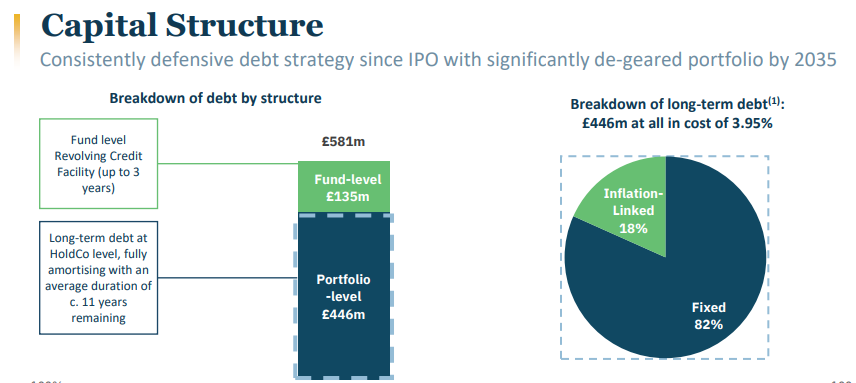

Debt

There’s no particular cliff edge to deal with, and the RCF of £135m has a three year life, and costs 1.85%+SOFR (so ~5.1%). The other debt is mainly fixed at 3.95%. Very competitive – and attractive.

The fund can earn leveraged profits on this debt – and does.

Depreciation and Interest Costs

Of course there’s no reason why 30 years is the limit for these assets, and life extensions and upgrades remain possible.

Debt is largely amortising and depreciation is 30 years so as subsidies naturally end at the end of their 15-25 years (the terms differ for each AR/CfD/FiT/RoC scheme) then so do corresponding costs reduce too.

Worse Than Milli?

It is also worth contemplating what life under a David Turver inspired government might look like. What if the government completely pulled the plug on subsidies? If Reform came to power that could be a vote winning policy – we’ll slash your bills etc etc – let’s reopen the mines and burn some coal instead.

If that happened, based on the current year accounts, revenue would approximately halve. Obviously the impact fades with each year and the earliest one might think this could happen would be 2029, unless the Labour government collapses.

The fund in FY25 would have earned £37m in FY25 (a 45.6% NOPAT margin) and £15m PAT, and paying over -£54m of dividends would be out of the question. Of course one wonders whether the ensuing chaos of such a policy change would lead to much higher electricity prices, and those prices would insulate a power generator to some extent.

You’d not be able to reopen coal mines and coal power stations quickly and what would energy generators do if the government did this? Stop generating? Or accept new terms.

Of course the other effect would be longer term picture of enjoying inflation-protected subsidy rises would be gone. That’s 50% today but grows to 64% of revenue which is subsidised by 2032 based on the effect of RPI increases (assumed at 3%)

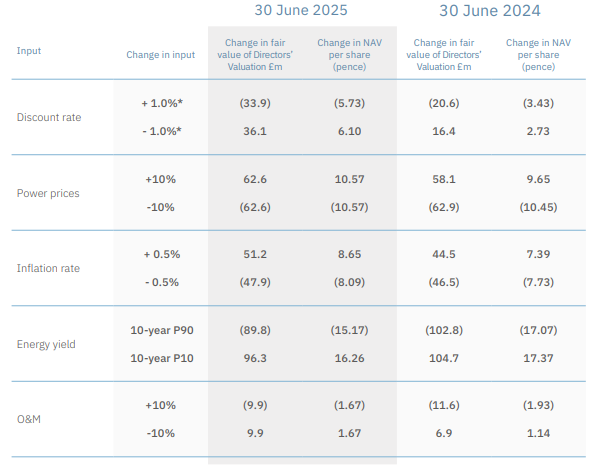

If inflation were higher than 3% in the coming years that would be worth 8.65p per share to BSIF in extra subsidies, and if the 3 leading power forecasters continue to be wrong then the current 15% higher power prices are worth 16p a share more to BSIF.

Conclusion

It remains quite unfashionable to be invested into these companies. There is a chance that the government will follow through on doing its dirty, so there’s a chance this share could fall lower – as harrumphers offload it once the consultation concludes. Although losing 1%-2% NAV when the discount is 40% seems an ok risk.

Equally though, there’s a chance the government would cave in – just like they have with many others. Will a £5 change to people’s energy bill change at a cost of torpedoing a cornerstone policy, be a vote winner? The farmers were celebrating a recent win against inheritance tax I believe, joining all sorts of public sector workers celebrating large pay rises.

You can offer reasons for and against the NAV being a bit more or a bit less than today’s current NAV. You can be like me and be pretty sceptical about the accuracy of power curves, or can be sceptical about government’s willingness to curtail inflation. BSIF would be a beneficiary to either. But if I’m wrong on either or both then it’s already priced in. It’s a one-way bet with no stake.

What I cannot see however is how BSIF would sell for below 40% less than its NAV i.e. to actually lose money in the event of a sale. Much like HEIT was like this.

Is the sale guaranteed? No. But if it didn’t happen even for a few years just relax and earn a covered 13% yield – well that’s a hardship isn’t it?

Regards

The Oak Bloke

Disclaimers:

This is not advice – you make your own investment decisions.

Micro cap and Nano cap holdings might have a higher risk and higher volatility than companies that are traditionally defined as “blue chip”