We ask when boards are going to bite the bullet and switch to value.

Thomas McMahon

Updated 12 Nov 2025

Disclaimer

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

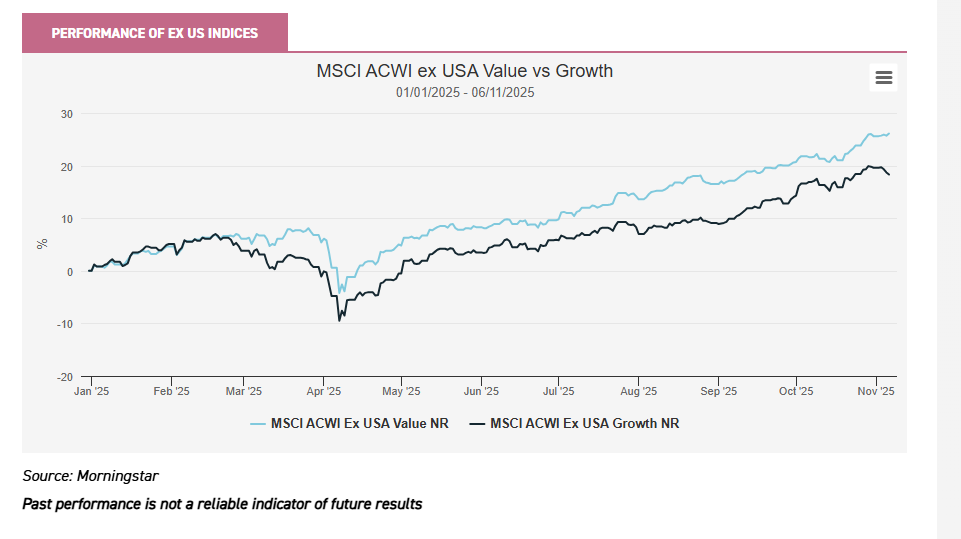

By now, most investors will have picked up on the fact that the main UK, European and Japanese indices have all outperformed the US index this year, in sterling terms. Despite the stunning returns to a handful of AI-related names like Nvidia, a weak dollar and, dare we say it, the better value outside America, has led to higher returns away from the US, the black hole that been sucking in all the headlines and the capital for the past three years. However, we wonder if many investors have realised yet that value has outperformed growth this year too? Well, to be clear, it is only outside the US that this is true: the MSCI ACWI ex US Value Index is well ahead of the growth index. This is true year to date, over a 12-month period and over three years, all thanks to a fairly sustained upswing in relative returns since February 2024.

PERFORMANCE OF EX US INDICES

Why has value outperformed?

We think this shows that the market is being driven by AI, not by growth, an important distinction. In the major developed world indices, AI-related stocks have been amongst the top performers – SoftBank in Japan, ASML in Europe – but this has not prevented the value indices from outperforming the growth indices in either of these two markets, or in the UK. Other factors have been driving good returns from stocks with no connection to the artificial intelligence trade.

One commonality is the strong performance of banks in all three markets. In Japan, sustained modest inflation and wage increases have seen gently rising interest rates for the first time in decades, creating a positive macro picture for the industry. In the UK and Europe rates have actually been cut, but they remain high compared to the pre-COVID environment, so a reasonably positive environment for their margins remains. Economic growth could also be characterised as ‘getting worse, but slowly enough not to matter’ – there are no great signs of distress in businesses, which are muddling through on the whole, albeit with weak earnings growth. The strength of the rally – Barclays is up 52% this year and Lloyds 65%, for example, seems to be about the ‘value’. Markets are slowly re-rating businesses from deeply discounted levels, creating the stealth rally phenomenon so common when value strategies are successful.

We think one other factor behind this stealth value rally is the rebalancing away from the US we have seen this year, to a large extent by American investors. Morningstar flows data shows sustained inflows into European equities since January. We think investors looking to sell expensive American stocks have been drawn to cheap areas of the market in Europe, the UK and Japan, rather than switching expensive European stocks for their expensive US ones. Banks are also an obvious first place to look for general exposure to a market or an economy, for any investor looking to rebalance away from the US.

How durable is this trend?

We have become accustomed in recent years to consider interest rates to be a key reason for the divergence in performance between growth and value in the pre- and post-COVID environment. If it was as simple as this, then the cuts that are expected in the US, UK and Europe would suggest growth will come back into favour. But in the long period of low interest rates there were other factors supporting growth equities too, one of which was the openness of global trade. Trade tensions and tariff barriers boost demand for materials and energy to build production and manufacturing facilities, increasing demand for products of typical value sectors. They also raise costs and therefore inflation, increasing the appeal of near-term cash flows by reducing confidence in the value of future ones.

Moreover, a less globalised world is one in which the opportunity for growth companies is smaller. Recent years have seen quality growth companies that were once kings of the market fall into disfavour, and the quality growth strategies that were so successful in the post-GFC period have struggled. Diageo, for example, may have had some internal issues, but its brands have been increasingly challenged by local names in China, like Kweichow Moutai. Similarly, the German automakers have been left behind in the electronic vehicle industry by companies like BYD, which is the largest seller of EVs globally. In fact, BYD accounted for 22% of electric and hybrid sales in 2024, with Tesla second at just 10%. BMW was fourth with 3.1% and VW seventh, with 2.6%.

The US’s largest economic concern at the moment has to be the race for AI dominance, not just because of the economic value in the industry but also the strategic importance of leading it economically as well as technologically. In our view, this fear is being ruthlessly exploited by Jensen Huang, Sam Altman and other executives in AI names who are looking to extract all possible support and subsidies out of the US government. We think the main concern for investors is that AI becomes another industry in which China copies, improves and surpasses its Western competitors. The success of Chinese alternatives to Nvidia, OpenAI and other companies in the value chain would materially reduce the potential cash flows for the US leaders, not only in China but in its potential customers, which could not fail to hit multiples via lowering expected growth rates, and therefore stock prices.

At the time of writing, some comments by key executives on the strategic importance of AI have spooked the markets, showing how vulnerable AI-related stocks are at very high valuations. Jensen Huang, president and chief executive of Nvidia, set the cat amongst the pigeons by saying that China “will win the AI race” before revising his comments to the softer “China is nanoseconds behind and the US must win”. Meanwhile, Sarah Friar, the chief financial officer of OpenAI suggested a government backstop for the financing of its data centre deals might be helpful (one friend asks if they will backstop his Wetherspoons tab too). We think it is obvious that these companies are lobbying hard, and using the Washington elite’s fear of China to gain an advantage.

More worryingly, OpenAI’s comments have been widely read as suggesting the company isn’t likely to find the funds elsewhere that are needed to finance its own operations for some time to come, and sounds suspiciously like an appeal for a bailout. They follow the announcement of a number of puzzling deals in the space with a slight circular outline. For example, Nvidia will invest $100bn in OpenAI to allow it to build data centres, for which it will buy Nvidia chips (with the money Nvidia has given it). OpenAI buys AMD chips and also receives warrants over its equity, which equity is boosted by OpenAI’s purchases. OpenAI will pay Oracle for cloud-hosting; Oracle will spend the money on Nvidia chips to run OpenAI’s services. Nvidia pays CoreWeave for cloud-services capacity, which will run on Nvidia chips, allowing OpenAI to use CoreWeave.

You don’t need to be a short-seller to get a little nervous about these deals. A vast amount of cash needs to be spent to fulfil a fraction of the promises that are being made to shareholders, and one of the major players in this series of deals, OpenAI, is unprofitable. Meanwhile Nvidia needs more and more cash to be spent on infrastructure if its own valuation is to be justified by growth rates. A cynic might suggest that the industry is trying to frighten the US government into becoming the next source of cash once the huge piles built up by the large-cap tech companies during the last 15 years have run out. Meta’s results last week saw a negative net cash position for the first time in years, for example.

Whether the cynicism is justified or not, the sharp correction seen in the share prices of Nvidia and related stocks shows how sensitive they are to changes in growth expectations. The 15% losses to Palantir shareholders last week give another example: the company is trading on sky-high P/Es, and seems to have taken a hit solely due to news that famous short-seller Michael Burry had a large short position in the shares.

In conclusion, we think there are plenty of signs that some sort of consolidation in the shares of AI companies will be necessary, if not a correction. For investors, there are two worries. The first is China taking the lead technologically and its companies winning market share and crimping the US champions’ growth potential, knocking the shares back. The second is the huge investment in AI infrastructure is not leading to profitable businesses using that infrastructure, and is therefore getting harder and harder to finance. In short, there is an awful lot of growth priced in to the shares of Nvidia and similar names, which means there simply isn’t the same scope for the shares to rise, even if the worst fears for the industry are misplaced. Nvidia’s impressive sterling returns of 34% are dwarfed by Lloyds’ 74%, for example. Investors don’t need to think artificial intelligence is going to fail to think the companies are going to underperform.

In our view, the chief bull case for value stocks, whether they be defined by sector – mining, oil, banks, utilities – or valuation metrics versus history, is that they are cheap and the artificial intelligence trade is over-extended. We don’t think the economic environment favours growth over value, but that the exciting new technology in the market has sucked in money chasing potentially huge growth. Now the shares have moved, a more realistic assessment is needed of the financial potential of the products. Investors have become massively overweight the artificial intelligence trade and the rebalancing of 2025 is likely to continue.

How to get exposure to value?

If this is reason enough to make sure you have exposure to value in your portfolio, it’s worth reviewing the options in the investment trust sector. Frankly, there aren’t that many left after a long period of growth outperformance, for one reason after another. We dug into the Morningstar database to look for those trusts with the greatest allocation to value stocks, which are defined by the average of a number of backwards- and forwards-looking financial metrics. Value stocks are roughly those in the cheapest third. There are only 16 out of 154 trusts for which there is data (the remainder are mostly invested in alternatives, real estate or private assets) with more than 50% of their portfolio invested in value stocks. Of these, ten are members of the AIC UK Equity Income sector (or the UK Equity & Bond Income sector of one).

The trust with the highest allocation to value is one of these, Temple Bar (TMPL). While an equity income strategy naturally leads managers into cheaper stocks, as they tend to have higher dividend yields, Temple Bar’s strategy explicitly targets value, with 75% of the portfolio in value stocks. This has helped the trust deliver exceptional NAV total returns, its 23.5% annualised over the past three years putting it in the top ten performers in the whole sector, behind mostly technology focused trusts and Golden Prospect Precious Metals (GPM), boosted by this year’s extraordinary rally in gold miners. Sector peer Aberdeen Equity Income (AEI) is a rounding error behind when it comes to value exposure, as the table below shows. Total returns haven’t been as good over three years, but in 2025 AEI’s NAV total return of 24.2% is close to TMPL’s 28.5%, and ahead of the UK market’s 21.8%. The rating of the share price is pretty close to TMPL’s though, with the trust on a small discount of 0.5% at the time of writing versus TMPL’s 0.8% premium. In fact, AEI has traded on a premium more frequently than TMPL this year, which we attribute to the exceptionally high yield. While manager Thomas Moore does target capital growth as well as yield, the trust really stands out on the latter metric, currently yielding 6%. It has been held back a bit this year by the mid- and small-cap bias, as it has been large-cap value that has really outperformed.

TRUSTS MOST EXPOSED TO VALUE

Source: Morningstar, as at 06/11/2025

We think smaller companies could be a potential source of opportunity in the next few years. If the rotation away from AI and the US continues, it could see a re-rating in the large-cap value areas that have been the first port of call, and investors could move on to small- and mid-caps to find deeper value. The managers of Aberforth Smaller Companies (ASL) have reported interest from US strategic and private equity buyers has risen over the past two years, with many taking advantage of rock-bottom valuations to acquire strong UK-listed businesses. But we think it is fair to say that this value argument hasn’t filtered through to the mass market investor, and UK small-caps remain deeply out of favour.

While ASL has outperformed the sector and small-cap indices over three years, returns have been more muted this year. Investors like to think of small-caps as a play on the UK economy, although this is a massive simplification and many UK small-caps are international earners. So, concerns about the UK economy may have been weighing on the market. However, as we have seen with the banks, if the bad news is all in the price, you don’t need good news for a re-rating. If investors start to look for value opportunities to diversify their portfolios, there could be no more obvious place to look than UK small-caps, and ASL and its stablemate Aberforth Geared Value & Income (AGVI) are the only two straightforward value options in the UK small-cap sector.

However, Fidelity Special Values (FSV) takes an all-of-market approach but has had a long-standing bias to small- and mid-caps, and manager Alex Wright’s contrarian approach means it could well benefit from any re-rating of cheap UK stocks in these segments. That said, trades in the large-cap space have been important to the trust’s success, including owning some of the UK banks, which he bought into when they were deeply out of favour. The strong performance means there isn’t the same discount opportunity as there is with some of its sector peers, with the discount at the time of writing being just 2%.

There aren’t many trusts investing outside the UK to have a strong value bias. Murray International (MYI) is one that stands out, with 60% exposure to value stocks. Positioning is generally contrarian, MYI having a long-standing underweight to the US on valuation grounds, which has been beneficial this year, helping the trust deliver NAV total returns of 24% as global developed market indices are up around 13%. MYI’s co-manager Samantha Fitzpatrick will be speaking at our online event, Real Dividend Heroes and Growth Giants, on 25/11/2025, and you can register to hear from her here.

MYI has long held a significant position in Asia and the emerging markets. Meanwhile, Henderson Far East Income (HFEL) and Fidelity Asian Values (FAV) are wholly focused on Asia and also have more than 50% in value stocks. HFEL is primarily an income fund, while FAV is a total return focused proposition run by managers with a contrarian approach. This has driven strong returns versus the benchmark this year, with an overweight to the cheaper Chinese market over the more expensive Indian market boosting returns in its recently reported results, as well as some good returns from idiosyncratic single stock positions.

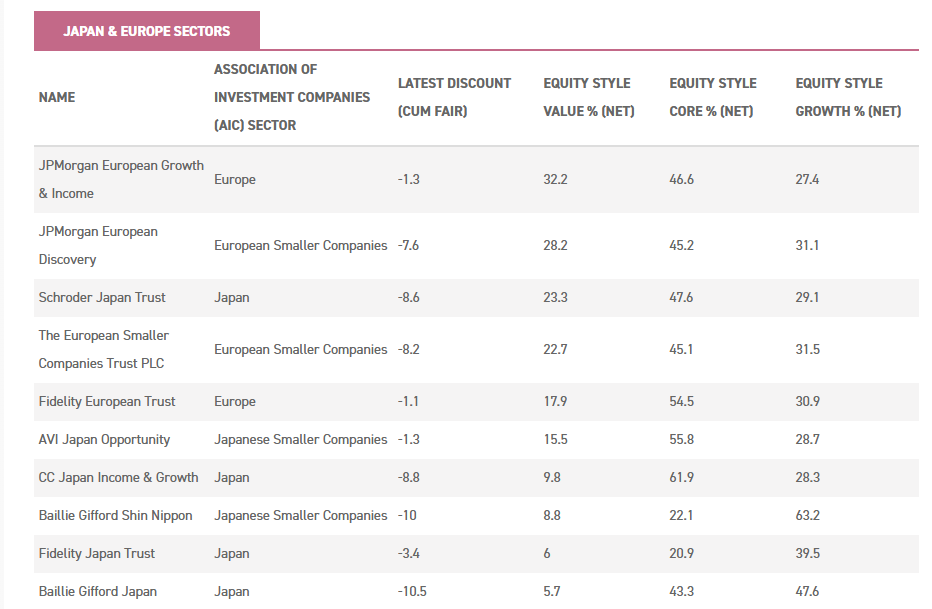

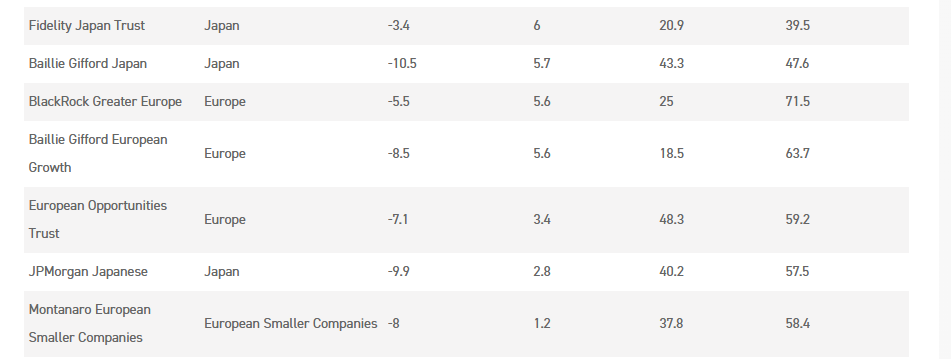

It’s notable there are no Japan or Europe trusts in the list of trusts with the highest value exposure. The Europe sectors have certainly become very biased towards growth. The trust with the highest exposure is JPMorgan European Growth & Income (JEGI), which sets out to provide core exposure, using a mixture of value and growth metrics to select stocks. The managers tilted back towards domestic European earnings this year, which may have increased the value tilt.

JAPAN & EUROPE SECTORS

Source: Morningstar, as at 06/11/2025

In Japan, there are a few strategies we would classify as value but don’t show up as such in the table. Schroder Japan (SJG) for example, has a stock-picking process that zeroes in on value and has led it to deliver strong performance under manager Masaki Taketsume. In the small-cap sector, we would highlight AVI Japan Opportunity (AJOT), which takes an activist approach to investing in deeply discounted small-caps. We think the data doesn’t show much of a value bias because the Japanese market includes some extremely cheap companies, so even a typical value strategy might not have to go into the cheapest stocks to find outstanding value, particularly if the manager is looking for an operationally strong business too. Additionally, AJOT’s approach is to invest, engage and watch the business re-rate substantially; if a business is being held through this life cycle, then towards the end of the holding period it may be showing lower value characteristics and higher growth characteristics.

Conclusion – Is value the next source of growth for the investment trust industry?

It’s clear that there aren’t many options for investors looking for a value approach left. We think this is why many of the trusts we have highlighted are trading on narrow discounts or indeed have been on slight premiums, even while the general perception remains that investment trusts are out of favour. Of course, those trading close to par are those that have shown good performance or a high yield, but we are suggesting that there is a good chance more of that will be produced by value strategies in the next few years. With so few value options to choose from, the upside pressure on share prices could become a pleasant problem for boards.

We should note, though, that the situation is not quite as bad as we have suggested. Our way of identifying a value strategy won’t capture all that could be grouped under that banner. We highlighted that a value strategy could easily lead managers into shares considered core by Morningstar, particularly when they re-rate. The data also can’t quite capture a portfolio such as that of AVI Global (AGT). AGT invests in companies with complicated structures that are trading well below their intrinsic value, which means mainly closed-ended funds, family-controlled holding companies and asset backed special situations in Japan. The managers’ assessment is based on their analysis of the underlying assets and their potential market value, which an analysis like Morningstar’s can’t capture. Indeed, over 25% of the portfolio isn’t graded growth, core or value by Morningstar at all. We think AGT could be a highly attractive source of growth opportunities if the market broadens out from the AI trade, and we provide a full update in the note we published this week.

In our view, boards and managers should be considering what new value strategies they can offer in the investment trust sector. The market currently seems under-served in most geographies, Europe in particular, and good performance by the value trusts should eventually lead to greater demand. It’s interesting to note the board of BlackRock Greater Europe (BRGE) appointing a new manager to the team in order to support the addition of some quality value ideas to the portfolio, citing the underperformance of growth in the current market; the board explains this was proposed by the manager, BlackRock. We think this might be a straw in the wind, and we might soon be seeing managers and private investors alike looking to increase their exposure to value.

Leave a Reply