Published on July 17, 2025

by Arthur Sants

Earlier this year, Warren Buffett announced he would be stepping down as chief executive of investment conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway (US:BRK.B). For more than 60 years, he has championed the importance of buying stocks based on their valuation rather the hype surrounding them. It was an approach that promoted discipline over speculation, and made him one of the richest people in the world.

The numbers are remarkable. Since 1965, Berkshire Hathaway has returned a compound annual gain of 19.9 per cent. This resulted in a total gain of over 5mn per cent, compared with 39,000 per cent for the S&P 500.

However, these total returns don’t tell the whole story. Berkshire Hathaway’s most successful years came in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. In the past decade, the business struggled to outperform a market that’s been driven by megacap technology stocks.

As a value investor, Buffett has never wanted to pay up for stocks he believed to be overvalued. Most recently that has meant not owning artificial intelligence (AI) company Nvidia (US:NVDA), which this month became the first business to be valued at $4tn (£3tn). As a result, in 2023 Berkshire Hathaway’s 15.8 per cent returns lagged the S&P 500’s 26.3 per cent growth.

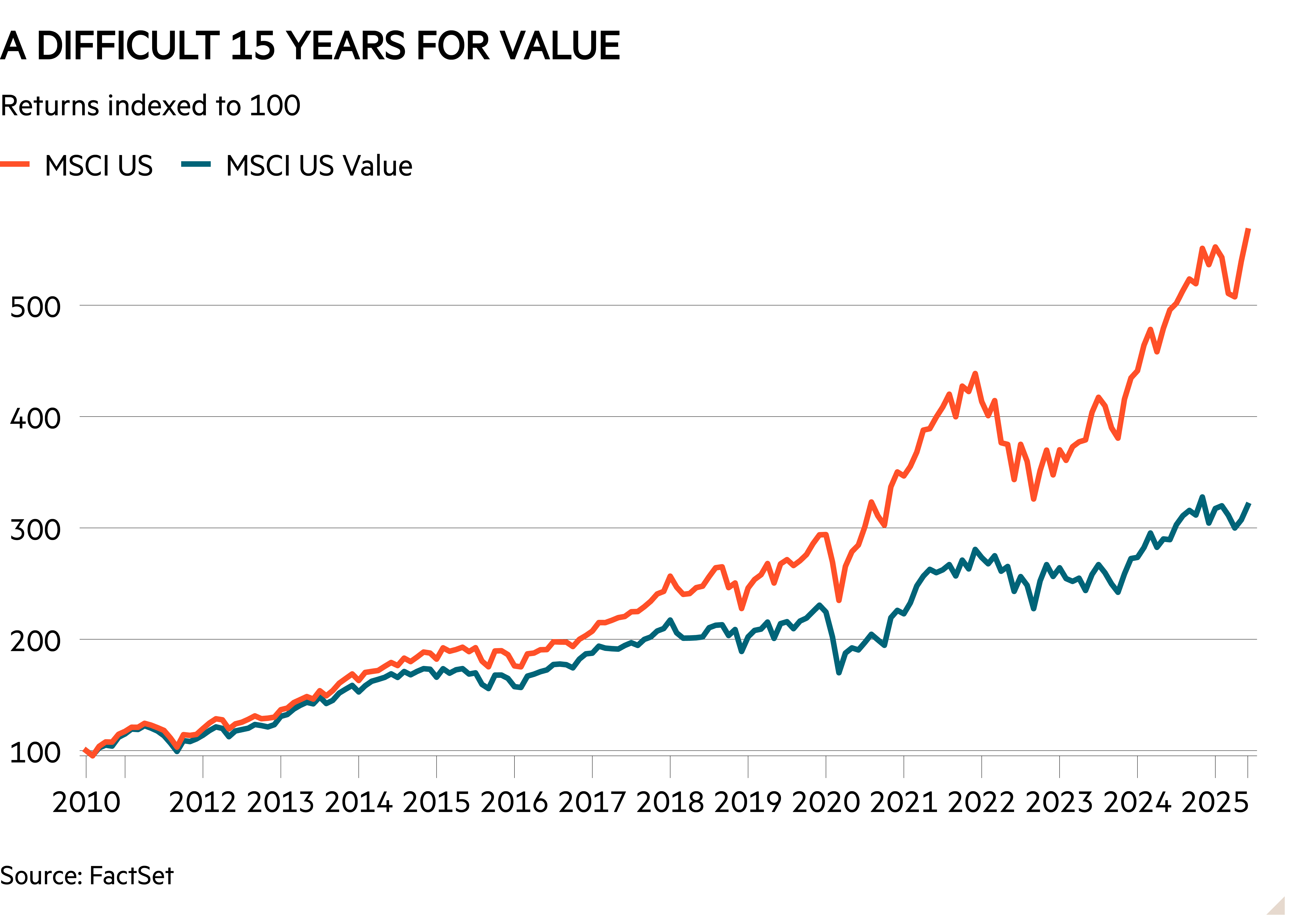

It’s been a similar story of underperformance for most of the value fund managers who see themselves as Buffett’s disciples.

In the 2010s, a well-established market theme said that low interest rates favoured high-growth stocks. The logic went that these companies, whose cash flows were further out in the future, were more vulnerable to higher rates. The longer an investor must wait for a stock to generate cash flows, the more risk-free returns (such as those offered by government bonds) they sacrifice.

Low rates meant that, when people questioned increasingly expensive stock valuations, the rationale was usually ‘Tina’: ‘there is no alternative’. In other words, with bond yields so low, the only place to invest was shares – including fast-growing but lossmaking technology companies.

Goodbye value investing

Value investors were one of the main victims of this investment regime. The concept of value investing was popularised by Benjamin Graham’s book The Intelligent Investor. In short, Graham’s philosophy was that investors should buy stocks that were cheap relative to their earnings and then hold them for a long time. For Graham, a shrewd investor is “one who bought in a bear market when everyone was selling and sold out in a bull market when everyone was buying”.

This is the opposite of a momentum investor, who buys stocks that are rising in value in the hope that other investors will also do so. “People talk about value versus growth [investing], but really it is value versus momentum,” says Ariel Investments fund manager Timothy Fidler. “Value is by definition a negative momentum expression, and momentum has definitely been the dominant force in the market.”

Investors’ Chronicle

For value investors, the hope was that when interest rates started to rise, stock fundamentals would become more important again. However, this hasn’t quite happened – at least in the world’s biggest market. While value shares have consistently outperformed growth in the UK since the rate-hiking cycle began, in the US the opposite is the case. US value indices produced far superior performance in 2022, coupled with a marginal outperformance so far this year. Cumulatively, however, the MSCI USA Growth Index’s 45 per cent return since the start of 2022 is almost double that of the value index.

The upshot is that stock market valuations have remained at record highs. The S&P 500’s consensus forward price/earnings ratio is 22, higher than it was at the start of the rate-hiking cycle.

The market continues to rise, as do valuations. The new rationale is that AI will shift earnings growth higher, but the outcome of that bet is still uncertain. This is either the beginning of a new era, where this time things really are different, or we are nearing the end of a years-long bull market.

On some metrics, the stock market is now as expensive as it’s ever been. “Equity valuations in the US have always been high, but rising interest rates make it obvious quite how high,” says Third Avenue portfolio manager Matthew Fine. “The equity risk premium is now negative, which means the anticipated earnings yield is expected to be lower than Treasury yields.”

Professional investors refer to the “equity risk premium” as the additional return that they demand for holding stocks instead of risk-free assets, such as Treasury bonds.

One way to estimate a stock’s expected return is to look at free cash flow yields. As the chart shows, at the start of 2020 the S&P forward free cash flow yield was 3.5 percentage points higher than the 10-year Treasury yield. This gap is expected: investors should be compensated for stocks’ greater risk with higher returns. The odd thing in the past few years is that the gap closed rapidly and, as with the gap between earnings yields and bonds, is now in negative territory.

Too much crowding?

The reason for the exceptionally high stock valuations has been the concentration of the stock market around a few megacap companies: the Magnificent Seven and a few others such as semiconductor designer Broadcom (US:AVGO). In total, the 10 largest companies make up over 40 per cent of the S&P 500.

This has made it a very difficult market for active managers, who pride themselves on picking lesser-known stocks, to outperform the market. “All of that has essentially created a ‘bear market in diversification’ because every manager that has de-emphasised the Mag Seven has created negative relative performance,” notes Fine. “The valuation spread between large and small caps has exploded to 40-year highs.”

Graham, who believed in the cyclical nature of markets, would have been sceptical of those who say AI’s potential to structurally increase earnings over the coming decades means “this time is different”. In his view, all bull markets had “a number of well-defined characteristics in common”. These included a historically high price level, high price/earnings ratios, low dividend yields compared to bond yields and much speculation on margin. All of these could be applied to today, suggesting the top of the market is not too far away.

Don’t time the market

Market bubbles have formed around technology narratives in the past, such as the ‘Nifty Fifty’ enthusiasm for IBM (US:IBM) in the 1970s and the dotcom bubble at the turn of the century. For many investors, it took years to recoup losses.

Timing is less of an issue for value investors, because they plan to hold their positions for the long term. “When I invest in a business, I do this with the assumption that there is no exit in sight; it has nothing to do with how much it will re-rate”, says Fine.

To find ‘cheap’ stocks, value investors need to be contrarian. This often means looking for businesses where something has recently gone wrong. To protect against the risk of a company going bankrupt, they can limit the downside by seeking out companies with strong balance sheets.

There is a strategy known as ‘deep value’, which involves buying an extremely cheap stock on the brink of bankruptcy. However, most fund managers look for businesses that still have strong business models but might have gone temporarily astray for some reason. “We try not to overpay, but we still want stocks with a strong balance sheet, good free cash flow and growth prospects,” says Janus Henderson value portfolio manager Justin Tugman.

Graham suggested buying stocks that trade at “a reasonably close approximation to their tangible asset value – say, at not more than one-third above that figure”. This advice is a little dated, given the rise of software and the increasing confidence the market has in these intangible assets. But the spirit of the suggestions – to compare the valuation relative to the balance sheet as well as earnings – still holds.

Fine has invested in carmakers BMW (DE:BMW) and Subaru (JP:7270), which are under pressure from tariffs and increased competition from low-cost Chinese manufacturers such as BYD (HK:1211) yet still have strong balance sheets and impressive cash flow generation. After recent share price falls, both their free cash flow yields sit at around 10 per cent.

As this suggests, Fine is increasingly looking outside the US for stocks that meet his “value” demands. “Japan looks like one of the most attractive areas and most notably there are a bunch of really well run and good businesses to own in a market where valuations have been beaten down,” he says.

As well as Subaru, his Japanese investments include semiconductor equipment manufacturer JEOL (JP:6951). Its electron beam lithography machines create the photomasks needed to etch semiconductors. The company is essential to the manufacturing process, but trades on a forward price/earnings ratio of just 11, significantly below many of its European and American peers.

But while value investors are confident in the stocks they own, many can’t say how long it will take for them to rebound.

“We have gone through 10 years of zero-interest rate policy. Then it looked like we would be in a more normal environment and then we decided we were going to enter this trade war, which has thrown everything into the mixer,” says Ariel Investments’ Fidler.

How long can this go on?

The AI story could continue to drive market concentration, while many of Trump’s economic policies favour larger international companies. In the case of tariffs, if nothing else the biggest companies can more easily lobby for exemptions. On top of this, the recent US spending bill is regressive, with a historically large cut to government healthcare insurance spending. This will take money away from low-income households with higher marginal rates of consumption; not good for domestic consumer stocks.

Although Fidler is confident that value investing will be profitable in the long term, he admits that “in the short run anything can happen”. One strategy is to pick stocks that have the negative impact of the trade war already priced in. The largest position in the Ariel Mid Cap Value fund is toy maker Mattel (US:MAT). The owner of brands such as Barbie and Hot Wheels sold off in the wake of “liberation day” because it manufactures many of its toys in China, as well as Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico and Thailand.

Mattel had previously “lost its way”, in Fidler’s words, but now it is concentrating on diversifying its supply chain and managing its costs. It is also successfully monetising its brands, most famously with the box office success of the 2023 Barbie movie. “We feel that Mattel has been unfairly penalised, but now it has found a way to utilise its brands in the digital age,” says Fidler.

A company does not always require negative news to be weighing on it to qualify as a value stock. Madison Square Garden Entertainment (US:MSGE) is the owner of the famous Madison Square Garden and has a long-term lease on Radio City Music Hall, both in Manhattan. Importantly, its free cash flow yield is 8 per cent. “The density of tourists means Billy Joel can play 40 Madison Square Garden shows in a row… there is an enormous margin of safety because of the valuation,” Fidler says.

Definitions of ‘value’ differ notably, to the extent that the Russell indices in the US allow stocks to sit in both growth and value benchmarks. Last month even saw Meta (US:META), Amazon (US:AMZN) and Alphabet (US:GOOGL) enter the Russell 1000 Value index, partly because their expected growth rates have fallen by more than that of the wider index this year. Even so, Russell continues to view all three as predominately growth stocks.

Many traditional value stocks are simply “not sexy”, notes Fidler, which nowadays also means they are often overlooked by the retail investors who make up an increasing portion of the market. In the first half of the year, retail flows into US shares and ETFs surged to a new high, reaching $155bn – the strongest first half on record, according to Vanda Research. Unsurprisingly, it was Nvidia and Tesla (US:TSLA) that were the most favoured stocks.

As a result, Janus Henderson’s Tugman says he often has to look for companies that operate in the “real economy” to find good value. One of his oldest and most successful holdings is Casey’s General Stores (US:CASY). It owns a chain of convenience stores, primarily serving rural and small-town communities in the Midwest, and has recently expanded into Texas. The business has been acquisitive, which has helped it generate roughly double-digit earnings growth in the recent past. “There has been a lot of consolidation in the US convenience store market, so it’s becoming a scarce asset,” he explains.

Is it the end of beginning?

The most famous value investors can’t always find opportunities, however. In recent years, Buffett has struggled to find “good businesses” at the right price. Berkshire Hathaway has grown so large that the only companies it can invest in to move the needle are other big businesses, which today are often trading at expensive multiples.

Instead, Berkshire Hathaway has increased its cash holding further in the past year.

However, Buffett, inspired by the lessons he learnt from Benjamin Graham, is still strongly supportive of the methods that grew Berkshire Hathaway to the position it has today and believes investors should always be looking for ways to deploy their cash.

This year saw the publication of Buffett’s final shareholder letter as chief executive, in which he continued to promote the importance of taking a long-term perspective. In 2024, Berkshire Hathaway made operating earnings of $47bn, but it chooses to exclude all capital gains on the stocks and bonds it owns, because the “year-by-year numbers will swing wildly and unpredictably”. Buffett reminded investors that his “thinking involves decades” and that “Berkshire almost never sells controlled businesses unless we face what we believe to be unending problems”.

If you take a long-term view, timing the market becomes irrelevant. It doesn’t matter about short-term fluctuations; to hold cash waiting for the right moment would mean giving up dividend returns. This is a point made by Graham in The Intelligent Investor, where he encourages readers to continue to invest whenever they have spare cash. Similarly, despite Berkshire’s growing cash pile, Buffett wrote that it would “never prefer ownership of cash-equivalent assets over the ownership of good businesses” because “paper money can see its value evaporate if fiscal folly prevails”.

Buffett has been a figurehead for value investing. He has argued that the only way to be successful is to research businesses in detail, understand them deeply and have the patience to resist market fluctuations.

With every year where momentum stocks outperform, the case for value stocks paradoxically strengthens. At some point, there must be a limit to the mindless growth of passive investing. The efficient market hypothesis argues that all markets are “informationally efficient” – meaning asset prices fully reflect all available information at any given time. But this is only true if people – or machines – are actively trying to process that information, rather than just following the crowd.

For Buffett, investors have an almost moral calling to try to allocate their capital efficiently. “One way or another, the sensible – better yet imaginative – deployment of savings by citizens is required to propel an ever-growing societal output of desired goods and services,” he wrote earlier this year.

In 2022, we were granted a peek into what could lie ahead – prior to the release of ChatGPT, the stock market sold off as interest rates started rising. In that year, the S&P 500 fell 18 per cent, whereas Berkshire Hathaway delivered 4 per cent returns.

There was once the belief that higher interest rates would force more discipline on the market. Whether by luck or design, the rise of AI has obscured that thesis. Value investors continue to wait for their time in the sun. They always knew they would have to be patient, but the surprise is quite how long the wait has been

Leave a Reply